Kragujevac is the fourth largest city in Serbia by population, based on data from the 2022 Census (which counted 174,583 people).

It is presumed to have been inhabited as early as the 11th century, but it is officially first mentioned in a Turkish tax register (defter) from 1476. After the Turkish conquests in the 15th and 16th centuries, the population in Šumadija region and Serbia significantly decreased, resulting in sparsely populated settlements. According to what I’ve read, in the late 16th century, the Ottomans began to establish a new settlement in this location, around a former market place, which then expanded on both sides of the Lepenica River.

The name of the city Kragujevac is interesting and there are only assumptions about its specific origin. However, the most popular version suggests that the settlement was named after a bird “kraguj”. Different sources provide varying information on which exact bird this refers to, as the term itself is practically only used in old texts mentioning birds used for hunting. This would imply it is some kind of hawk or falcon (Accipiter genus), but there are also those who believe it could be referring to the griffon vulture. There are also assumptions that the origin of the city’s name comes from entirely different sources, but ultimately, that is not as important anymore. The fact is that two heraldic kragujs (single-headed eagles) can be seen on the coat of arms of Kragujevac.

This city on the banks of the Lepenica River is located in central Serbia, quite literally so. Looking at the map, Kragujevac is situated roughly halfway between the northern and southern borders, as well as between the western and eastern borders of the country.

It is also important to mention that Kragujevac was the capital of Serbia from 1818 to 1841.

Like the rest of Serbia, Kragujevac has gone through various phases over time, primarily marked by numerous military activities and conflicts. This has led to frequent destruction and deterioration of the city and its parts. Time itself has been a crucial factor in all of this. Additionally, a combination of, what seems to me, Serbian excessive neglect and the proverbial lack of funds for investing in historical and cultural landmarks (sometimes a real issue, sometimes just an excuse), as well as a frequent absence of awareness about the importance of preserving old significant structures and actively engaging with them, plays a significant role.

All in all, based on my observations while visiting cultural monuments in Kragujevac and walking around the city, looking at various buildings in early spring of 2024, my impression is that they clearly reflect our typical stance on these issues. Some monuments are in catastrophic condition, some are almost “invisible” and certainly underutilised or not appropriately adapted, but there are also outstanding examples.

There are also some buildings that appear exceptionally beautiful to me, but evidently they are not considered important enough to be systematically renovated, allowing their full beauty to shine through. Perhaps the owners lack the funds, interest or motivation to make any changes. While I can understand much of this, it saddens me deeply as well. Often, especially when Serbs travel to Western Europe, we return with stories of wonderful and well-maintained cities where everything is meticulously kept. However, these impressions rarely serve as a catalyst, inspiration or paragon for improving things here at home.

We may not have grand palaces and castles, nor millennia-old pyramids and temples, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t anything valuable worth preserving and restoring. On the contrary, there are numerous smaller, less lavish yet equally beautiful, significant or attractive structures, as well as hidden treasures stored away in museum storerooms, which for one reason or another are not widely known or adequately promoted.

As one friend of mine, who is very knowledgeable about this topic, says: “We have such a wealth of cultural heritage that in the end, we have a ‘beautiful girl’ problem.” What she means is that it often happens that when a girl is very beautiful, everyone admires her and she grows up in such an environment like a “beautiful doll” without feeling any need to further develop herself intellectually or spiritually.

I’m not sure if it is exactly like that, but it often seems to be the case. Be as it may, I diligently explored Kragujevac and eventually visited all the cultural monuments in the city listed by the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Serbia. Except for one.

That one is the archaeological site Todorčevo – Strna žita, which I marked on the map, along with the other immovable cultural assets that I did visit. (By the way, in the end, I realised I also missed another cultural monument, but I’ll write about that – in the end.)

I have mentioned earlier that I have given up searching for archaeological sites because they are often researched by experts and then conserved, but not necessarily developed for tourist visits. First, I’m never sure if I’m in the right place when searching for them and, secondly, there is usually nothing visible on the surface.

At the site of Todorčevo – Strna žita, excavations have revealed remains of several settlements layered on top of each other – the oldest dating back to the 5th millennium BCE, the second from the 10th century BCE, and the youngest from the 3rd and 4th centuries CE.

Regarding other immovable cultural assets in Kragujevac, I first visited the buildings on Svetozara Markovića Street, where several structures have been designated as cultural monuments.

So, I first went to the house at Svetozara Markovića 5. During my visit, it was surrounded by a construction fence along with the adjacent plot (where house number 3 once stood) because a new building was being constructed there. However, from what I could see based on the project displayed at the construction site, the new modern building and its immediate surroundings will encompass this old house, which ideally should not be disturbed except for restoration purposes.

House at Svetozara Markovića 5

House at Svetozara Markovića 5

In any case, this house, where it seems no one currently lives, was built in the 1820s in a style typical for houses in Serbian cities of that period. It housed an advisor to Prince Miloš, as Kragujevac was the Serbian capital at that time.

The house was constructed using the half-timber technique, although this is not visible due to the facade. It features a hipped roof covered with Monk and Nun roof tiles, and it stands out with a porch in the front adorned with wooden railing and pillars. There is a plaque on the house clearly stating that “this historical monument is protected by the state.”

On Svetozara Markovića Street in Kragujevac, there are as many as five houses from the first half of the 19th century, but there is considerable confusion in the documentation (both written and cartographic) regarding the numbering and location of these houses. I diligently began researching (sometimes the positive aspects of an obsessive personality type) and at the spot marked on the map I had, I searched for the next old house but I only found a couple of buildings belonging to the Red Cross of Kragujevac and where the local Ombudsman for the city of Kragujevac has their offices.

Buildings at Svetozara Markovića 7

Buildings at Svetozara Markovića 7

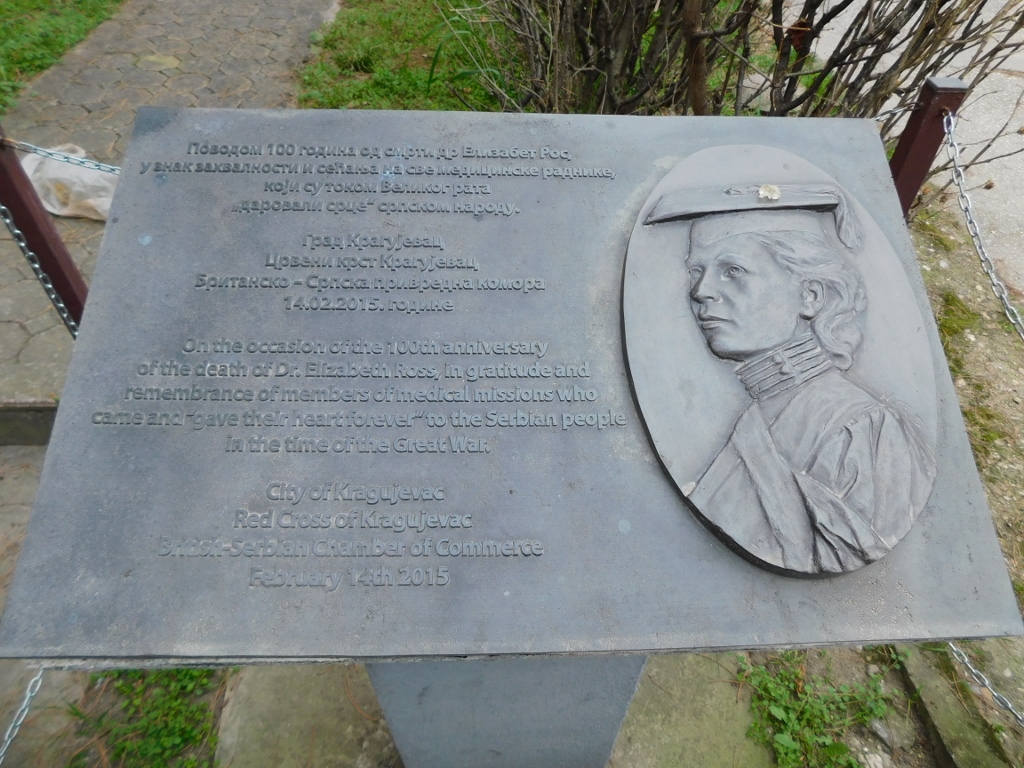

My research was not in vain. Although I did not find any old houses specifically at this location, I came across a plaque dedicated to the Scottish doctor Elizabeth Ross (1878-1915). In 1915, during World War I, she came to Kragujevac at the invitation of the Serbian government to treat soldiers and civilians afflicted with typhus. Unfortunately, she herself contracted the disease and passed away on her 37th birthday in Kragujevac, where she was also buried.

Plaque honouring Elizabeth Ross

Plaque honouring Elizabeth Ross

Elizabeth Ross is not a unique case and several other women doctors, specifically from Scotland, stayed in Serbia during WWI to treat both soldiers and civilians. I have previously written about another such example from Mladenovac (see: https://www.svudapodji.com/en/mladenovac-arandjelovac/).

As for the old houses, already at the next number, at Svetozara Markovića 9, there is officially another cultural monument, the house of Dr. Ilija Kolović from the first half of the 19th century. Dr. Ilija Kolović was a physician of the Kragujevac County and a member of the national assembly who passed away from typhus in 1915, just like Dr. Ross, while treating others for the same disease. His house represents another important immovable cultural asset. But is that really the case? Not quite. Here, I came across a completely dilapidated house. I was shocked!

House at Svetozara Markovića 9

House at Svetozara Markovića 9

From what I’ve managed to find online, the owner of the house (who bought it in 1989) had wanted to renovate it and had previously approached the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments, but they “did not allow her to make any changes to it.” The house was significantly damaged in a fire in 2020. I don’t know what happened next between the owner and the institute, but the “resourceful” owner took matters into her own hands on 1 May, 2023, without any permission, hired an excavator and decided to demolish the house with the intention of “building an identical one out of sturdy materials” (as she told reporters). I haven’t heard anything so foolish in a long time.

If it were up to me, and of course it’s not, those responsible for destroying cultural monuments should have to pay for the complete restoration. It wouldn’t be a problem even if they didn’t have the money – there’s something called work/labour, even if it’s forced. Because of such a crime, because this is a crime against the culture and history of the entire nation, they should have to work to repay the restoration, no matter how long it takes.

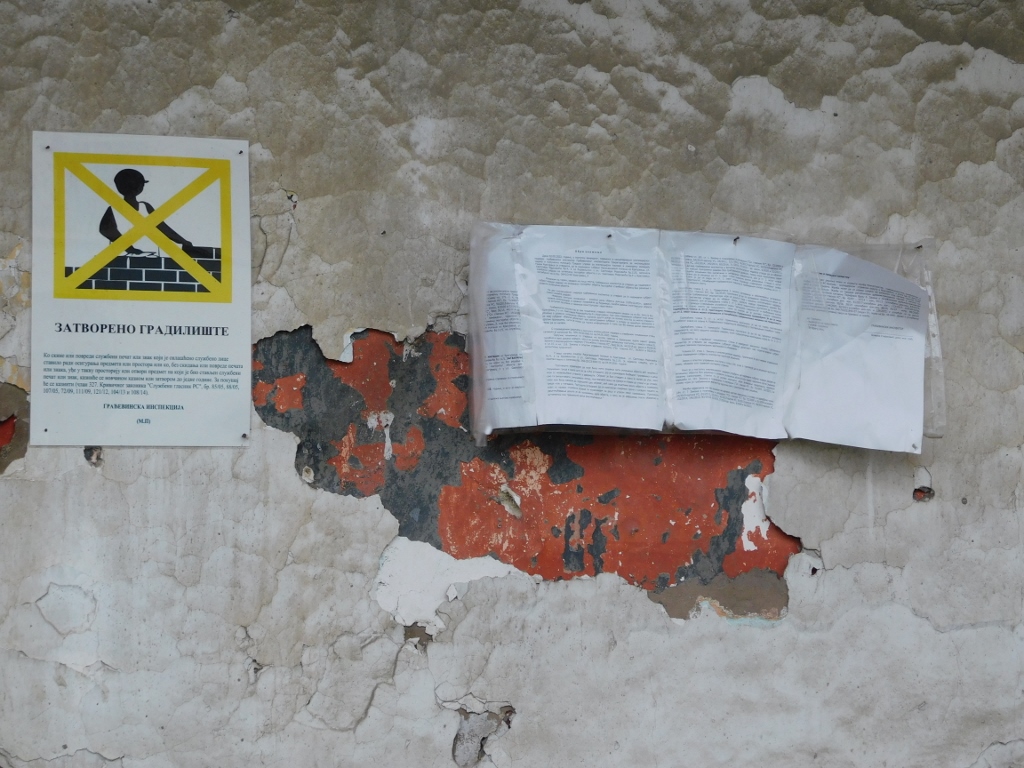

The only thing that gave me some comfort while here, suggesting that Serbia is not completely lawless as a country, was that there had obviously been a building inspection and the “construction site” had been closed down. Since there was a fence, I couldn’t easily approach and read the documents posted on the wall of the house.

House at Svetozara Markovića 9, a detail

House at Svetozara Markovića 9, a detail

Judging by the condition of the rear part of the house, it is clear to me that the building had not been properly maintained and that it indeed deserved to be properly renovated.

House at Svetozara Markovića 9

House at Svetozara Markovića 9

Not only does this house, along with the other houses on the street from the same period categorised as cultural monuments, present an extraordinary example of architecture in Kragujevac during the period of Serbia’s liberation from the Ottoman Empire, but this particular house also had its own specific features that made it very valuable. Among other things, it had richly decorated pillars on the porch (part of which can be seen in the first photo), its ceilings were made of small matched boards and it had interesting arched doors in some rooms. The house was typically built using the half-timber technique (which can be seen a bit in the previous photograph) and it also had a multi-pitched roof covered with Monk and Nun roof tiles. I can only hope that it can be saved.

On the adjacent plot, at Svetozara Markovića 11, there is a two-storey building that is a part of the “Radoje Domanović” primary school, with a plaque indicating that it is an endowment of Milovan Gušić.

Building at Svetozara Markovića 11

Building at Svetozara Markovića 11

Plaque on the building at Svetozara Markovića 11 (“Endowment of Milovan Gušić (1823-1891)”)

Plaque on the building at Svetozara Markovića 11 (“Endowment of Milovan Gušić (1823-1891)”)

A part of today’s “Radoje Domanović” primary school includes the “Old School in Kragujevac - Endowment of Milovan Gušić” (the official name of yet another cultural monument). However, based on the documentation I used, including the description of the building, this is not the building seen in the photo above, but rather a single-storey building in the neighbouring street (the primary school complex spans across two streets). In the following days, I visited as well that other building that also bears a plaque stating it was the endowment of Milovan Gušić.

Right after the newer part of the “Radoje Domanović” primary school, at Svetozara Markovića 15, there is a plot with a house from the first half of the 19th century called the “Kosovska prizemljuša” (Kosovo-style ground floor house). It is named after its construction style, but it is not known to whom it originally belonged.

House at Svetozara Markovića 15

House at Svetozara Markovića 15

By the way, the chaos in the documentation regarding house numbers applies in this case as well, so it can be found listed as “House at Svetozara Markovića 17.” The fact is that house numbers in Svetozara Markovića Street in Kragujevac have changed (and not just there, but I’ll write about that later on), however, corrections have been made only for one cultural monument in this street.

House at Svetozara Markovića 15

House at Svetozara Markovića 15

So, this particular house, which has always been used for residential purposes, doesn’t have any special architectural features beyond the half-timber construction style and a hipped roof covered with Monk and Nun roof tiles. However, it is considered significant primarily due to its historical period, dating back around 200 years when Kragujevac was the capital of Serbia.

I walked by several times here and I took a photo of this house while standing on the other side of the street as well, which provides a specific perspective on the house itself, the plot, the fence and also its position in relation to the primary school building on the left side of the photo.

House at Svetozara Markovića 15

House at Svetozara Markovića 15

By the way, on this sunny day, I passed by the demolished house at Svetozara Markovića 9 once again. It was a very poignant and sad sight. That house is a cultural monument.

House at Svetozara Markovića 9

House at Svetozara Markovića 9

But let me return to something more positive and certainly the most successful story regarding these old houses.

Right next to the house at Svetozara Markovića 15, there is another one that is also a cultural monument, built in the first half of the 19th century (it has three numbers in the documentation - 7, 17 and 19). I checked on the spot. This is the house at Svetozara Markovića 17, also known as Denin konak (Dena’s Residence).

Houses at Svetozara Markovića 15 and 17

Houses at Svetozara Markovića 15 and 17

This house was originally built for Nedeljko Stojković, better known as Knez Dena (Chieftain Dena), who served as a state official during the time of Prince Miloš. The house is constructed in the half-timber style, featuring a gently sloped hipped roof covered with Monk and Nun roof tiles, and it is notably distinguished by its elevated porch with wooden pillars and a railing made of matched boards. What makes the story of this house successful is that it has been well preserved and maintained (at least visibly from the outside) and over time, a restaurant has been opened here.

House at Svetozara Markovića 17

House at Svetozara Markovića 17

I’ve heard from people in Kragujevac that this is a pretty good restaurant; I just didn't have the time to visit, which I regret. I’ll definitely make it a point to come here during my next visit to Kragujevac, even if it's just for a coffee if time doesn't allow for more.

Another feature of this house is the covered well located right next to the street. It can be seen in the next photo I took on a sunny day.

House at Svetozara Markovića 17

House at Svetozara Markovića 17

Finally, a few plots further down, there is another house from the first half of the 19th century, also categorised as an immovable cultural property of exceptional significance. In the documentation, it is listed as “House at Svetozara Markovića Street 23,” although there is a correction indicating that it is actually at number 21 (which is accurate).

House at Svetozara Markovića 21

House at Svetozara Markovića 21

The house includes basement rooms and there is also a porch on the side wall in relation to the street with an entrance to the house.

House at Svetozara Markovića 21

House at Svetozara Markovića 21

The foundation and basement walls of the house are made of rubble stone, while the walls of the house are made of brick, which sets it apart from the previously mentioned houses.

The house was originally built for Archpriest Miloje Barjaktarović, but what makes it a monument of exceptional importance is the fact that Svetozar Marković (1846-1875), an influential Serbian socialist, publicist and political activist, lived and worked here from 1873 to 1875. The entire street is named after Svetozar Marković after all.

Today, this house hosts the ethnographic section of the exhibit at the National Museum of Kragujevac. However, like in the case of other major museums in Kragujevac, what makes its organisation and accessibility for visits and public engagement notably poor is its opening hours.

The museum “Kuća Svetozara Markovića” (House of Svetozar Marković) is open four days a week, excluding weekends, from 9 AM to 3 PM! In other words, this is the time when the adults are supposed to work, while children and the young go to school or university. It raises questions about the target audience for these museums – perhaps the unemployed or retirees?

House at Svetozara Markovića 21

House at Svetozara Markovića 21

In any case, with this I finished visiting the old houses that serve as a testimony to the architecture in the former Serbian capital Kragujevac and other details located in Svetozara Markovića Street.

Further down the same street, there is another building that represents a cultural monument, but more about that and other cultural monuments of Kragujevac in the next sequel of my travel stories.